Return to Canyon Dave Tour Pages

or the Nature and Geology Pages

*********************************************

List of Grand Canyon Rock Layers

What is Grand Canyon Stratigraphy?

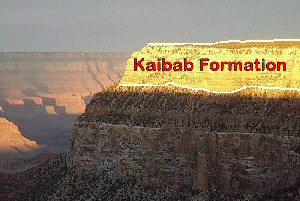

Kaibab Formation

Toroweap Formation

Coconino Sandstone

Hermit Formation

Supai Group

Redwall Limestone

Tonto Group

Muav Limestone

Bright Angel Shale

Tapeats Sandstone

Vishnu Complex

Kaibab Formation

Permian Period, 270 Million Years Old, 350 Feet Thick.

Light gray to tan

cliff at the canyon rim.

The Kaibab Formation was named after the flat Kaibab

Plateau that lies at 7,000 to 8,200 feet above sea level. Kaibab is a Southern Paiute Indian word meaning “mountain lying

down.” The Kaibab Formation is composed of sedimentary rocks: limestone, dolomite,

sandstone, and chert, deposited under a shallow inland sea.

The Kaibab Formation was named after the flat Kaibab

Plateau that lies at 7,000 to 8,200 feet above sea level. Kaibab is a Southern Paiute Indian word meaning “mountain lying

down.” The Kaibab Formation is composed of sedimentary rocks: limestone, dolomite,

sandstone, and chert, deposited under a shallow inland sea.

Some of the other Grand Canyon layers were terrestrial,

deposited on land. But all were deposited on a flat landscape near

sea level. Much

later, geological processes raised the Grand Canyon area to its present

altitude of 7,000 feet at the South Rim and

8,200 feet on the North Rim.

Among the bottom-dwelling or "benthic" creatures

of the sea, such as clams, corals, and snails, the shells are most commonly made of the mineral

calcium carbonate (CaCO3). After many years,

waves and currents break down or dissolve most such shells.

Among the bottom-dwelling or "benthic" creatures

of the sea, such as clams, corals, and snails, the shells are most commonly made of the mineral

calcium carbonate (CaCO3). After many years,

waves and currents break down or dissolve most such shells.

The remains of the shells will eventually

be deposited to form an ocean-bottom mud known as "ooze". Over the milennia, the ooze hardens

to form the rock types called limestone and dolomite. A few surviving shells

may be preserved as fossils, but most become crushed or dissolved and are

no longer recognizable.

Most

limestone is gray in color. The Kaibab Formation at the South Rim is made of

limestone, but the limestone here contains much sand. This is because the

sandy shoreline of the Kaibab inland sea was usually less than 20 miles east of Grand Canyon,

and beach sand washed into the ooze while it was forming. Because of

the sand, the Kaibab Formation shows a sandy tan color.

Chert is a minor rock constituent of the Kaibab Formation. Chert is a hard, brittle rock made of silica

(SiO2) that often forms as lumps or “nodules” within limestone beds.

Chert can be almost any color--gray, white, tan, red, green, and even black. Chert has been useful throughout the human

ages: it was the chief tool-making

material of ancient people worldwide. Most of the arrowheads you have seen

were probably made of chert.

Chert is a minor rock constituent of the Kaibab Formation. Chert is a hard, brittle rock made of silica

(SiO2) that often forms as lumps or “nodules” within limestone beds.

Chert can be almost any color--gray, white, tan, red, green, and even black. Chert has been useful throughout the human

ages: it was the chief tool-making

material of ancient people worldwide. Most of the arrowheads you have seen

were probably made of chert.

The brown spheres and lumps of chert in the Kaibab

Formation are mostly made from the silicious cherty

skeletons of ancient sponges called Actinocoelia. The brown dots in

this photo are chert nodules containing Actinocoelia.

This chert nodule contains a white sponge fossil, Actinocoelia. Chert is very hard, so the sturdy

chert in the

Kaibab Formation causes this layer to resist erosion. In a sense, the lowly

sponge protected the Grand Canyon, because this top canyon layer shields all the

layers beneath.

This chert nodule contains a white sponge fossil, Actinocoelia. Chert is very hard, so the sturdy

chert in the

Kaibab Formation causes this layer to resist erosion. In a sense, the lowly

sponge protected the Grand Canyon, because this top canyon layer shields all the

layers beneath.

This little story pretends that people were alive when the Kaibab Formation was laid down. But it was long, long before people. It was 270 million years ago. The story's purpose is to immerse ourselves in the time period--to imagine that we were a tribe living in the environment of the time. Why do this? Because to imagine these ancient times--to even try--is to better understand the majesty of time's march.

Our Tribe in Kaibab Time

Here at the future Grand Canyon, the sea has encroached from the west and the shoreline is in the east, so at the moment we are swimming in 100 feet of salt water. There are sharks and bony fish in these waters. Invertebrates and seaweed thrive on the bottom.

Everything has that salty, fishy, tide pool smell. The sea floor is thick with sponges: we collect them for trade

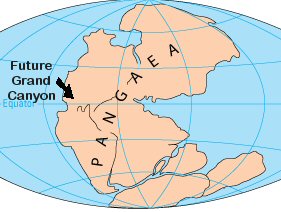

in Pangaea, our world continent. On our world map to the right, perhaps you can make out the shapes of some continents that

will one day appear. But our people know nothing of this.

Everything has that salty, fishy, tide pool smell. The sea floor is thick with sponges: we collect them for trade

in Pangaea, our world continent. On our world map to the right, perhaps you can make out the shapes of some continents that

will one day appear. But our people know nothing of this.

The shifting shorelines of the Kaibab Sea will come and go, intermittently covering the Grand Canyon area.

But from our tribe's puny human perspective, the shoreline will be just as it is "now", for ever and ever. A thousand years

is nothing to the ages of the earth, but we have myths that our ancestors lived here

then. In another thousand years, our descendants will collect their sponges. It will always be like this.